URL: https://www.desy.de/information__services/press/press_releases/2014/pr_300114/index_eng.html

Breadcrumb Navigation

Faster X-ray technology paves the way for better catalysts

Researchers observe a catalyst surface at work with atomic resolution

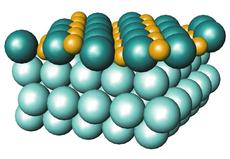

Scematic illustration of the catalyst's surface. Credit: Johan Gustafson/Lund University

Hamburg, 30 January 2014. By using a novel X-ray technique, researchers have observed a catalyst surface at work in real time and were able to resolve its atomic structure in detail. The new technique, pioneered at DESY's X-ray light source PETRA III, may pave the way for the design of better catalysts and other materials on the atomic level. It greatly speeds up the determination of atomic surface structures and enables live recordings of surface reactions like catalysis, corrosion and growth processes with a time resolution of less than a second. “We can now investigate surface processes that were not observable in real time before and that play a central role in many fields of materials science,” explains DESY researcher Prof. Andreas Stierle. The Swedish-German research team around lead author Dr. Johan Gustafson of Lund University present their work in the US journal Science.

Materials scientists currently lack a method to record data of the full atomic structure of surfaces during dynamic processes within a reasonable time. Existing methods are either too slow or require ultra high vacuum, prohibiting the flow of gas in the test chamber and thus ruling out a live investigation of dynamic reaction processes involving gas phases at near atmospheric pressures.

“Our goal was to observe surfaces under reactive, application-oriented conditions in real time,” says Stierle. The team used the high-energy X-rays from DESY's light source PETRA III. When X-rays strike a solid material, they are diffracted into a characteristic pattern that yields information about the atomic structure of the material. In conventional X-ray measurements performed at lower photon energies, the sample and the detector must be rotated to map out the full diffraction pattern painstakingly step by step, a procedure that can easily consume ten hours or more.

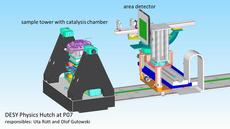

In contrast, the high-energy X-rays of PETRA III are scattered into a much smaller angular range, producing a much more compact diffraction pattern that can be recorded at once with a high-end two-dimensional detector at the High Energy Materials Science measuring station P07. "This approach makes it possible to record data 10 to 100 times faster,” explains Stierle. As a consequence, scientists can gain a full surface structure in less than ten minutes or track individual structural features with a temporal resolution of less than a second. “It also allows us to more easily identify unknown or unexpected structures,” underlines Stierle.

For their investigations, the researchers installed a test chamber, in which the gas pressure can be up to 1 bar — the same as normal atmospheric pressure — to approach realistic reaction conditions. A mass spectrometer allows for on-line monitoring of the gas distribution within the test chamber during measurements.

To demonstrate the new approach, the researchers watched a catalyst of the precious metal palladium live at work: a two millimetre thick palladium single crystal with a diameter of one centimetre converts toxic carbon monoxide into harmless carbon dioxide, much like catalytic converters do in cars. The technique enabled the scientists to observe how the palladium began to convert the carbon monoxide (CO) into carbon dioxide (CO2) as soon as oxygen (O2) also flowed into the chamber. “We can watch how the catalyst switches from a non-reactive state into a reactive one,” explains Stierle who heads the NanoLab at DESY and also holds an appointment as professor at the University of Hamburg.

The researchers hope to identify the catalyst’s active phase by using this new approach. For decades, scientists have debated whether the conversion of carbon monoxide into carbon dioxide, for example, takes place on the bare metallic surface, on an oxide layer, or on oxide islands on the surface. “The new technology gives us the opportunity to identify the reaction centres in real time at atomic resolution,” says Stierle.

In the end, the findings could be used to optimise catalysts. In general, catalysts are substances that accelerate chemical reactions without being consumed by them. The new X-ray technique has a wide variety of applications for materials research. The scientists expect completely new insights into the kinetics of surface processes, enabling the design of new materials on the atomic level. “The combination of the extremely bright X-ray source, the sample environment and the 2D detector at PETRA III is worldwide unique,” emphasises Stierle.

The new X-ray technique has been jointly developed by researchers from Lund University, DESY, Chalmers University of Technology in Gothenburg and the University of Hamburg within the Röntgen-Ångström-Cluster and received financial support from the German Federal Ministry of Research BMBF within the project NanoXcat.

Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron DESY is the leading German accelerator centre and one of the leading in the world. DESY is a member of the Helmholtz Association and receives its funding from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (90 percent) and the German federal states of Hamburg and Brandenburg (10 percent). At its locations in Hamburg and Zeuthen near Berlin, DESY develops, builds and operates large particle accelerators, and uses them to investigate the structure of matter. DESY’s combination of photon science and particle physics is unique in Europe.

Reference

“High-Energy Surface X-Ray Diffraction for Fast Surface Structure Determination”; J. Gustafson, M. Shipilin, C. Zhang, A. Stierle, U. Hejral, U. Ruett, O. Gutowski, P.-A. Carlsson, M. Skoglundh, E. Lundgren; Science, 2014; DOI: 10.1126/science.1246834

Science contacts

Prof. Andreas Stierle, DESY, +49 40 8998-2005, andreas.stierle@desy.de

Media contact

DESY press officer Thomas Zoufal, +49 8998-1666, presse@desy.de

Images

|

Combination of the detector images from the measurement where the structure of a single layer of palladium oxide is formed on top of a palladium crystal. In this combined image scientists can identify the signature of the oxide film as well as the underlying metal. Credit: Johan Gustafson/Lund University |

View of the palladium single crystal mounted in the test chamber. Credit: Johan Gustafson/Universität Lund |

|

Experimental setup at the High Energy Materials Science Beamline P07 at PETRA III. The X-ray beam enters from the left, hits the sample and is recorded by the detector (right). Credit: Uta Rütt, Olof Gutowski/DESY |

Video

The video shows the response of the surface structure to the flow of carbon monoxide and oxygen into the test chamber. As soon as oxygen starts to flow into the test chamber, carbon monoxide is converted into carbon dioxide. Credit: Johan Gustafson/Universität Lund